After My Dad Died, I Became An Avid Collector Of Vintage Trans Photographs

The first image of "the dynamic duo" was only the beginning. Once I started looking for proof that trans joy has existed forever, I couldn't stop.

What a Thursday! (Notably, the day of the week that none of you chose as one you would want to be named after, even Andy and Charlie, who I thought might jump in and grab poor Thursday - but no.)

A huge thank you to Amos for writing me a while back with the idea of contributing to AJPT and then following through so beautifully with this piece today. You know you can write me also if you're interested in being published here - at Jane@anotherjaneprattthing.com.

I love Amos and I love you too.

-Jane

PS Ok, you know I can't be that brief and have to tell you my inner dialogue about this already-inner dialogue intro: I had another piece set to run today, but I felt like it was very heavy and we have been running heavier topics recently. So I'm giving you a break from that today with Amos’ fascinating and uplifting story and will run the other one tomorrow or soon, but I do love to hear what you like and don't like and whether you think we run too much sad or dark stuff.

BIG PPS: Coming up this week, we are publishing an unexpected epilogue to our best-read AJPT series ever. So get those subscriptions done so we can email that to you as soon as it is ready. You're gonna love it.

By Amos Mac

When I found the photo of the dynamic duo, I wasn’t on the hunt for trans joy. I kind of cringe at that term. (Sorry, don’t cancel me.) It sounds so polished, so Instagram-facing –too simplified for what it means to find happiness in a world actively trying to erase us. Maybe I can’t have nice things. Maybe I hate joy. Oh my god, wait, do I hate joy? I don’t! I even consider myself to be “joyous” on occasion.

But the dynamic duo —a name I gave the two people in the photo, standing by a tree stump in crisp suits— was who I’d been looking for my entire life. It was a clue that the past might’ve been queerer than we’re told. Or maybe it was a flicker of familiarity: an image that made me feel less alone. Their faces —round, soft, tough, with dark hair peeking out from under their hats— look a lot like my younger, pre-transition self.

“They’re crossdressing,” the vendor at the convention center photo show told me with a smirk, tossing air quotes around the “crossdressing” like he’d solved a mystery I hadn’t asked him to solve. I handed over five bucks and slipped the photo into a hard plastic sleeve for safekeeping.

Later, at home, I considered what the vendor said. Sure, they could be crossdressing. Dressing up outside of your typical gender presentation was a popular thing to do, even in the 1920s. A way to blow off steam and make memorable photos with friends. But what if it’s a “yes, and” situation? What if the duo were blowing off steam and trying on a part of themselves that lived inside them at the same time? What if this photo was the only play around with, this feels right, even if they didn’t have the words for it?

The photo is old. 1920s, maybe earlier. The two friends look dapper. Confident. Hats, ties, hands in pockets. Facing each other with that masculine flair I was drawn to in teen magazines as a kid, when I’d rip out glossy posters of Luke Perry and the New Kids on the Block and study their body language like sacred texts.

At first, collecting snapshots felt like a quiet little side hobby. I started by looking for something specific: queer-coded haircuts, tender glances between “roommates,” couples in matching sweaters by the Christmas tree.

What began as a scavenger hunt turned into something else: a personal archive of photos where queer, trans, and gender non-conforming people are seen—by me. All speculative, as a way I connect to the past.

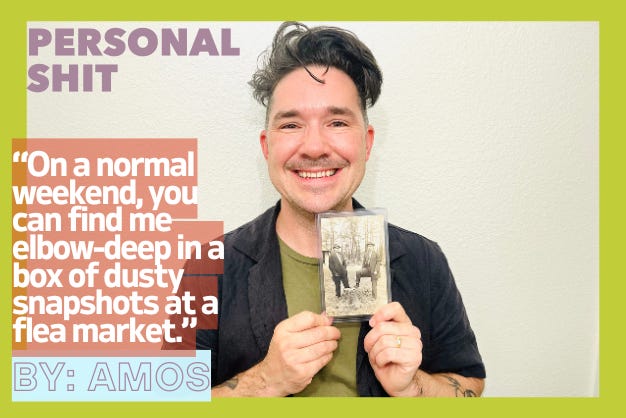

On a normal weekend, you can find me elbow-deep in a box of dusty snapshots at a flea market, often in a town where people are more likely to collect rusted farm tools than the remnants of someone else’s great-aunt’s photo album. The further away from a major city you go, the better.

It started during the 2023 WGA strike, not long after my father passed away. Not only did I have extra time on my hands, but I was grieving, and poring over antique family albums my dad had stored away. I inspected every face, scanned every page for hints of familiarity in these photos. Even though I was related to the people in the photo albums, I didn’t know them, or feel connected. They all appeared so heteronormative. Where were the secret queers and artist freaks in my family?

Unfortunately, using visual cues from the inherited photo albums, I didn’t see any. But I wanted to see them. So desperately. I knew queer and trans people have existed since the dawn of time. And with no TV writing jobs or show pitches on the horizon, I started to focus on found photographs – what they could tell me about my own history as a trans man.

I picked up a single mid-century snapshot at an antique mall of a buff military dude striking a cheeky pose and bought it for a dollar. Then, at a reseller’s liquidation, I pulled out 40 photos of two elderly women, both voracious bowlers from the 1980s, (who I can only assume had a romantic relationship due to their matching holiday sweaters, multiple Siamese cats, and romantic embraces), purchased them and placed them in an envelope together for safekeeping.

When I discovered a crumbling 1940s photo album with the covers ripped off at a Burbank estate sale in a room that reeked of cat pee and took it home (inside I found a single photo of a young queer couple folded inside a piece of paper, hidden) I realized I was a collector. I doubled down– vowing (to no one but myself) to never stop looking for a past I knew was out there.