It Happened To Me: I Got Hit By A Drunk In A Truck. I Learned And Forgot That A Few Hundred Times

I acquired the same type of brain injury former representative Gabrielle Giffords suffered when she was shot in the head.

Hi lovely AJPT people,

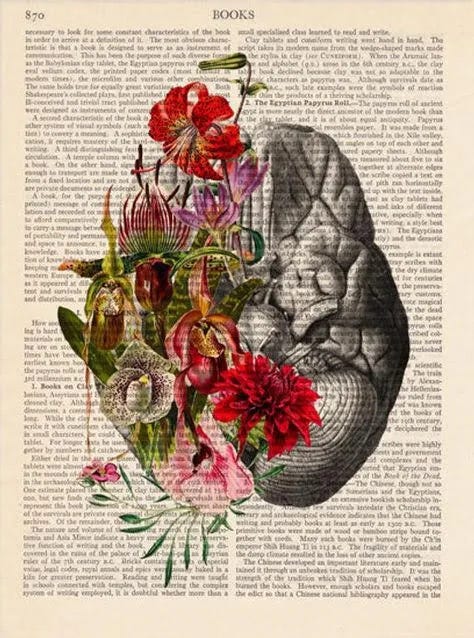

I'm going to save my little updates for you until tomorrow, because I want to give all the attention today to this beautiful post. Working on this with Judith has been working with a true artist. (Growing up with two artists as parents, this is my highest compliment.) She is also incredibly thoughtful - she knew how much I love “Brain On Dictionary” (see it below) and sent me a copy of it out of the blue this morning with just the note “For You.” I cherish it.

If you love Judith’s work as much as I do, you can find her writing about this and other topics lots of other places, but I highly recommend you subscribe to her own Substack that is linked at the bottom of the post.

Have a wonderful wonderful Wednesday and beyond.

Jane

By Judith Hannah Weiss

On the last day of my first life, I got in a car and never came back. At about the same time, which was 10 AM on a Tuesday, a woman named Mrs. Cream ran out of breakfast beer. So she stole a truck, crashed into a storefront and crushed a parked car. I was in the car.

I came to on a freezing table in a paper gown. I was afraid of the metal taste, the tilting room, the deafening roar of a nurse, the techs tweezing glass from my skin. Someone in scrubs asked if I knew why I was there. I pointed to my head. Someone else asked if I knew my address. I pointed to my head again. It was a Code 4 emergency, which means my life was threatened. Then it wasn’t my life.

The next time I came to, my head was in a helmet studded with electrodes. Probes punctured my scalp to survey my mind. Temporal lobe, occipital lobe, there was a probe for the lobe. The good news is I survived. The bad news was brain damage.

One moment I was in the semi-glamorous often brutal if-you-can-make-it-here-you-can-make-it-anywhere feel of Manhattan in the 80s, 90s and early naughts. The Vanity Fair-New York-Tina Brown-Devil-Wears-Prada years. I freelanced for each of them. The next moment, I was in a-funny-thing-happens when you’re extracted from a wreck. Or rather, a not funny thing that locked me in a life no one would choose with a brain no one would pick.

Me in 2006, a few months prior to accident

I pointed to a shoe because I couldn’t say “shoe.” Or I pointed to my head. I needed words I didn’t have to say words I couldn’t say. That is called aphasia. Imagine you are trying to speak and no one can understand you. That's what it's like to live with aphasia. Imagine you are with other people and you can’t understand them. That’s what it’s like, too.

My brain had been repeatedly sliced by the sharp bones inside the skull, resulting in "the single broadest gap" the doctor had ever seen.

You might wonder how it feels to wake up one day and not know who you are. I don’t know. I don’t remember. You lose short-term recall, long-term recall, words, space and time. Or you recall a fragment of something, but find it and lose it almost at once. That is called amnesia. My body was 56 when my new brain arrived. Someone new was in my place. Someone new who had my face.

A tester asked me to name the months of the year. I said October or Tuesday or Mary or May. Footing? None. Anchor? Are you kidding? Another tester tells me to push a lever. The right lever or the left. This would help quantify what was left of my right brain. Pixelated pieces of my first and second life shot in and out of my skull like projectiles, which was especially strange when you consider the size of my skull.

They asked me to point to a picture of a teapot, an apple, a plate, a spoon. This is called “confrontational naming” and means I need to know what things are and what they’re called. They asked me to recall a sequence of two things moments after I see it. No dice. Then a “sequence” of one. No dice again.

Me in early 2007, a few months after the accident, when I tried to cover the right side of my face.

They tested my head hundreds of times and found lots of things had disappeared. Like the file that encodes new memories and the file that integrates physical movements so you don’t fall out of your chair. I mean so I don’t fall out of mine. The parts of my brain that were broken could not be stitched together. The parts of my spine that were smashed could not be unsmashed.

My first mind was bankable. It did things like pay the bills. Now words try to arrange themselves letter by letter, in the right order in the right subject in the right city and century. My “graphomotor set-shifting,” and my “visual integration” are described in reports as extreme, devastating, severe. I was impaired and could not be repaired. The doctor told me so. She spoke with all the sensitivity she likely lost over years.

There were other problems, too. Between September and December – within three months – I lost my life, my mind, my child, my mom, my career, my income, our home, my friends. I waited to see when I would be better. Then I waited to see if I would be better. Then I waited to see how much better I would be. Four months after the accident, a very tall doctor with icy eyes stated that scans showed “diffuse axonal damage in multiple parts of the brain.”

This meant my brain had been repeatedly sliced by the sharp bones inside the skull. Like they were Ninja blades. Evidently, the resulting scores presented "the single broadest gap" she had ever seen. The frosty physician had a semi-British accent, or perhaps just wanted one. She was about 6 feet tall and stood most of the time. I am just over 5 feet tall and was seated. She said that while my verbal scores were in the high 90s, other scores were in their 20s. Which seemed to me like somewhere between a rock and a toad.

Brain on dictionary. Image by author.

I became an outpatient and was installed in Brain Injury Group. I called it Ow-Patient group for a while, which seemed quite apt to me. We were missing persons, missing the persons we used to be. Some of us were lawyers or teachers or preachers or cooks or custodians. Some were parents. Some had parents. Some had toddlers. Some spoke like toddlers. Some were attached to machines.

The larger group was divided into two smaller groups, one for survivors of brain injury and one for caregivers. I was the only “survivor” in Outpatient Rehab who was a “caregiver,” too. I took care of me.“We” tried to get “me” to doctors’ appointments, outpatient rehab, out for a walk. In clean clothes, with cellphone and keys. “We” tried to keep a calendar. “We” tried to use a keyboard. “We” tried to button a shirt. “We” tried to read a book. Mostly “we” could not.

At the end of year one, I was ejected from the program because things were “as good as they could get.” Or because I ran out of insurance. Mostly, I think, due to insurance. I was told I could attend other very pricey programs I could not afford. One of them, in Richmond, Virginia, had two Saudi princes felled by polo and the son of a Russian oligarch.

On my last day, someone in scrubs told me to raise my eyebrows. Then to spell HELLO. Then to spell GOODBYE. Then to spell them both backwards. Then to say numbers backwards, which meant you must turn 9, 12, 24, 7 into 7, 24,12, 9. Even though in real life no one has ever asked me to say anything backwards.

I relearned how to walk, how to talk, how to boil water and not burn myself, how to fry eggs and not burn the pan, how to get feet in pants, how to climb steps and descend them, how to keep my head from wobbling, how to make upper and lowercase letters. Then I forget. They need to replace the memory board. The logic board. The chipset. The plug-ins. They can’t. Perseverance is the hard work you do after the hard work you've already done. And so, at the age of 56, I learned to read. Or rather learned to read again, with the gentle help of no one at all.

Post-ejection, I turned to Google to find how to act normal, how to be normal and how to seem normal when you’re not. First, I held a book in my hand. That was a big deal. Then I touched the pages. That was a big deal. Then I read the same pages for nearly a year. At first, they meant nothing. Then they meant something, for a few seconds.

If I began where I’d left off, say on page 5, and found a character was on a train, I had no idea why she was on it or where she was going. Then I tried to write. Words flocked together or flew apart, flappy-winged, and tried to land. Endearing juxtapositions so transfixingly, transportingly wrong, you for sure wouldn’t find them anywhere else. Then I began to build a book, and it began to rebuild me.

At about that time, I began making pictures. I started with very small collages (2.5” x 2.5”). I coped best and was most pleased with small things. They did not require recall, theme, sequence, or storyline, and I made just one of each. I liked making things I could see and touch, things that stayed themselves.

Paint and collage by author

Nineteen years post-truck, I still emigrate between the land of pretty-smart and the land of not-smart-at-all. I am still chronically either underestimated or overestimated. I frustrate others by leaning on them and by not leaning on them, by asking or by not asking them. I baffle them when I seem normal, and when I don’t.

Stacks of books I had loved might as well still be stacks of books I had never read. I didn’t know if I’d read them or not. Ditto if I’d seen films or not, even films I loved. Ditto again, songs. And places. And poems. I still speak and write with the urgency that comes when time is short.

Brain trauma is not about the past: the successes, accomplishments, accolades. It’s not even about losses. It’s a muddy, rutty, hands and knees crawl up to the first rung of the ladder, and up each rung after that. The climb does not and will not end. Even if someone clears your chakras with crystal samurai swords, you will still be brain damaged. There is no final healed bone or mended tear of the skin or cure.

I still wake up at times drenched in sweat, dreaming I’m compressed in a car, trying to kick my way out. This means some of anything I know still drops out of anything I am trying to say as I am trying to say it. I try hard not to say things like, “in one swoop fell,” when I mean, “in one fell swoop.” Then I try hard not to say, “little what to read when.” Or “when this sky is bending down and tying his shoe,” when I mean “when this guy is bending down and tying his shoe.” Sometimes I say something right. And I keep painting birds.

Judith Hannah Weiss lives south of Charlottesville, Virginia, where she also makes art for humans and homes for birds. You can find her at Dispatch from Bewilderness.

.

Wow ... just, wow. What a story of survival. It brings up so many feelings for me, even though I have never been in a situation such as yours. It reminds me to practice gratitude and not sweat the small stuff but it also brings up a lot of feelings or anger towards people who act so carelessly and selfishly that they can take so much from a person in the name of a beer. Thank you for sharing your beautiful story and I hope that every day is easier for you than the last.

Judith, I've already said how much I love this piece. Your writing inspires me and so many other writers too to be better writers themselves. One thing I have not had a chance to do is read your writing from pre-truck days, and I would love to do that and compare. I'm curious how you think about the differences between your writing now and then also. Thank you, thank you thank you for the beautiful work.