I Married The Wrong Man. And I Knew It.

This is a love story.

Hello dreamy people,

A funny (not haha) thing: When someone you know very well unsubscribes from your Substack without saying anything. Then keeps corresponding with you and asks you to do a favor promoting their Substack. I think people don't realize that I see EVERYTHING that goes on with AJPT. And that I care about EVERYTHING to do with AJPT. (I have been obsessive like that since Sassy days when I would sit on my office floor with a literal mailbag for hours reading through the piles of purple-felt-tip-penned reader letters with the hearts over every “i”.)

I also hate sweeping under the rug or pretending or ignoring (I'm going to blame that on being Scorpio, because most of my combative traits seem to be able to be excused that way, so I'll just try it again here, whether it’s accurate or not). So what would you do in that scenario?

I just realized something else after writing that last sentence, which is that when I want to do something nasty or retaliatory, I tell you guys the story here and ask you to do my dirty work for me (like HERE just the other day and HERE when I needed a response to a rude text I got inadvertently and HERE too, that time the BigTime Editor wrote a heartfelt note tearing me apart and saying AJPT was “below me” - I will decide what is below me, thank you very much, and there’s not much there). Then I can just blame the response on my crowdsourcing if my message is particularly ill-received. Thanks, partners-in-crime!

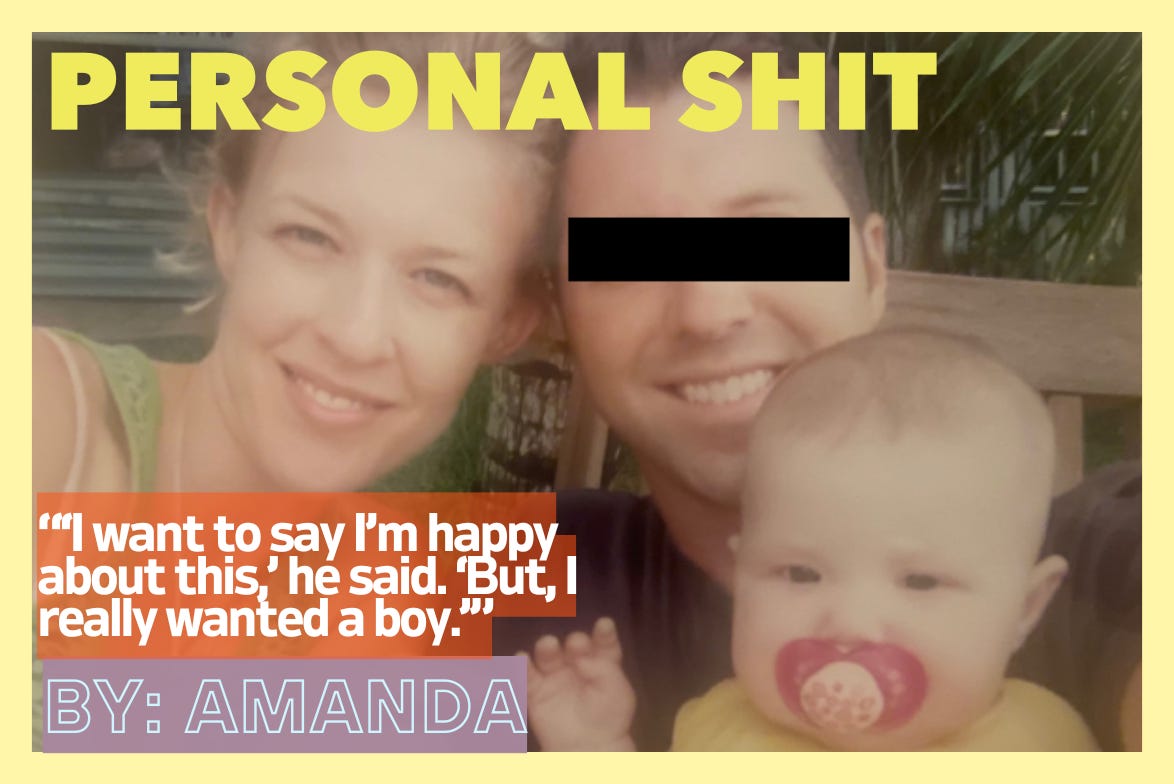

Today's featured story from the wonderful (and wonderfully named) Amanda Jane is such an amazing ride (I refuse to say “journey,” even when it is probably the appropriate word). I love that you've gotten to know Amanda through her stories about getting divorced, living with her parents after the divorce, and most recently eyelid surgery. But not in any linear order. So today's is also about a major aspect of her life that is again not in any kind of chronological order based on her other AJPT pieces. I hope you love it just as much as you have her past contributions. I related to this piece more than any story about motherhood I have ever read personally. Big thank you, our Amanda Jane.

On a related note, I'm doing something I've never done before here on AJPT, where I generally think that the writers’ personal images are so important to establishing that these are real people telling their real stories. Reading this one, I kept envisioning the scenes as if they were happening to me in my own life. I thought it would be interesting to try at first running this with only these two basic images and letting your imaginations do what mine did as I read it, creating those worlds inside our heads like when we're reading fiction that we remember so well we can have dreams set inside them decades later. So after you tell me what you think of this pared-down approach, I'll come back and add in the usual array of visuals that illustrate the people and places Amanda is writing about. But if you like it clean like it is, let me know that too. I'm interested in either case.

And you: You're a dream.

Jane

PS Speaking of Scorpios, my birthday is the 11th so get ready to be really really really nice to me all day. Even if you have to be mean to someone else or skip a date to get good sleep the night before or whatever, make it your priority. Thanks! And why is it always shitty weather on my birthday every single year??

By Amanda Jane

I married the wrong man. On my wedding day, if someone had put a gun to my head and said, “Is this the person for you? Tell the truth or I’ll shoot,” I would have said “no”. Still, I try to live my life without regrets. But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to understand why I did what I did. The story that follows is the closest I have come to an honest explanation.

There is a curse on every child raised in New York. With the City as the standard against which everything will forever be compared, it is nearly impossible to appreciate most other places as independent entities. I rebelled against this tendency. When I was eighteen, I left New York for college in Louisiana, and I never returned, deciding to stay there for graduate school and, after that, to settle in south Florida.

“Settle” is an interesting word, as it can refer to either putting down roots, or sacrificing and, in my case, I was kind of doing both. I knew that people I’d grown up with saw my decision as peculiar. New Yorkers don’t just leave for places like Louisiana or Florida, not for as long as I did, not without a good reason – or a better reason than mine. Mine was that I wanted to prove that a city had nothing to do with the person I was, that I could be a happy, whole, interesting person anywhere.

Towards the end of college at Tulane, I started dating Jon, who was also from New York, but hated it, and never wanted to return. I didn’t share his feelings, but I was on board with giving a brand new existence a try. It was fun to play house with him, to find a Garden District rental that was bigger and cheaper than anything we could have afforded in the City. We found like-new furniture at the thrift store, got a dog together, found jobs with health insurance and direct deposit. It felt like a life, or the beginning of one.

Things weren’t perfect. The neighborhood was good for New Orleans but that is not saying much. Our street smelled like garbage whenever the wind blew, and the house occasionally had mice and always had roaches, likely due to the hole in the bathroom floor which went straight through so you could see the street below.

Also, Jon and I argued. It was never explosive but it was frequent. Still, I do remember laughter, mostly mine. And frustration, also mostly mine, and mostly because I would be laughing one minute and we’d be fighting the next. I remember going to bed angry many nights, and fantasizing about leaving, a lot, but I never did. It would seem bad enough to leave and then, suddenly, it wouldn’t. We always talked things out, always made up. Always a calm after each and every storm.

We left New Orleans to attend graduate school at LSU in Baton Rouge. Jon went to vet school and I pursued a master’s degree in exercise physiology. Baton Rouge was even more of a cultural departure from New York than New Orleans had been. When I arrived, I finally felt like I was in the South even though I’d already lived in Louisiana for six years. I made sure not to talk to the people I met in Baton Rouge about religion or politics or why I had recently decided to be a vegan. It was hard to make friends, but I did, eventually. And this taught me that you don’t need to talk about God or the government to be friends, a lesson I’d never have learned had I stayed in the City and one I’ll forever be grateful for.

“Becoming a parent had not been his desire, but he hadn’t wanted to break up and this meant that we wouldn’t need to.”

After finishing school in Baton Rouge, Jon took his veterinary board exam in Florida. South Florida seemed a reasonable place to move; it had good weather like Louisiana but more of a northern mentality – at least it did in 2003 – despite being geographically even farther south. After Jon passed the exam and got his license, it felt like there was no turning back, at least not without significant hassle.

We got married as soon as we moved to Florida. It wasn’t so much a proposal as it was a decision. I liked the idea of us truly belonging to one another — of proving this to ourselves and our families. Our relationship was far from ideal, but I thought that if we agreed that we officially belonged to one another, we’d fight less. I thought that if, at the end of each day, there was no easy way out, we’d have no choice but to make it work. This logic was flawed but, strangely, my plan succeeded. Or almost succeeded. Some of the time. Not never.

We rented a house in Fort Lauderdale, a newly renovated, one-story, canal-side home with a pool shaped like an amoeba and a terra cotta tile roof. We found jobs in Florida, bought cell phones with 954 area codes. After a year of renting, we bought the house we were living in, so we now shared a permanent address, a mortgage.

Once, when the receptionist at my job left a note for me that said “call home,” I immediately got nervous, thinking that something had happened with my parents. But I soon realized she’d meant my Florida home. This was the first time in my life that I remember feeling like an adult.

I had done it. I had made my home in a new place, in not-New-York, in Elsewhere. I started making friends – good friends– people who laughed at my jokes, people who got me, people who I learned to care about, to love. And I liked the little town we lived in, Wilton Manors, which was inside of Fort Lauderdale, surrounded by canals. I liked that it had a part-time volunteer mayor and a guy named Charles who always answered when you called City Hall, that you didn’t just get a recording with a bunch of extension options. I liked that the town had a slogan, “Life’s Just Better Here.” It wasn’t, not really, but sometimes it kind of was.

When I was twenty-nine, I ended up in the hospital with a burst appendix and, eventually, sepsis. (This might be a good opportunity to talk about the substandard healthcare in Florida versus New York, but I think it’s too much of a diversion.) During my two weeks as an inpatient, I went off of birth control pills and decided to stay off, reasoning that one day I would want to get pregnant.

But when I stopped taking the pill I did not get my period back. And as is often the case with things you take for granted and then lose, I went from assuming that I would have a baby “one day” to wanting a baby more than anything in the world. No. “Want” does not begin to describe it. It was a need – like food or sleep or air. When the longing took over my body, usually in the late afternoons, I would curl up in a ball on the bed, hugging my knees, crying about the loss of a life that had never existed. It was a full-on tantrum. I not only wanted a baby – I was acting like one. But I couldn’t stop, and I didn’t really want to.

I have often asked myself why this need was so strong. Was it just that I felt I’d never be able to have a baby and therefore wanted one more? Was it driven by my reproductive hormones? Or was it that having a child in Florida would have been the final step in permanently establishing the roots I had been craving? The reason I wasn’t getting my period was biological, but it almost felt karmic to me, like perhaps I’d made a mistake in moving so far from my family and was being punished for it.

“I was a mother without a child – an inverse orphan.”

Other women my age weighed the pros and cons of having kids like they were deciding between hanging curtains or installing blinds in their living rooms. They talked about what they were going to have to give up – their careers, their social lives, their toned bodies— to raise a child. I could not relate. How could you weigh these costs against gaining a part of your soul you felt was missing? I didn’t care any more about any of the things I already had. I wanted to throw them all away, like the clothes in my closet that didn’t fit right. I wanted to sacrifice, to discard, to never look back. Given the choice of limbs or a child, I would have chosen the child. I didn’t care what I’d look like after childbirth or how I might not ever advance in my career or how much money we would have or not have. I was a mother without a child – an inverse orphan – and I needed a baby to give myself to, my whole self. You’ve heard about biological clocks? Mine was Big Ben.

It was a long couple of years. I was working as an exercise physiologist at a hospital. It felt like every other lunch break, I would be walking through the over-air-conditioned, linoleum-floored halls of Holy Cross on my way to see one specialist or another. I got diagnosed with polycystic ovaries, blocked fallopian tubes, a thyroid condition, suspected cysts on my pituitary gland. One fertility specialist wanted me to try in-vitro fertilization. Another said I needed to start with a surgery to un-block my fallopian tubes. A third recommended fertility drugs and artificial insemination.

I would dream about my baby. Sometimes, she would be a real person but, other times, just a penciled sketch or a swirl of smoke or nothing at all – just a feeling. But then I would lose her, every single time – down the drain after my bath, in the lining of my purse, at the bottom of my bowl of soup. After I woke up from one of these dreams, I couldn’t shake the feeling of loss, my thoughts clouded and gray and heavy as I helped patients up onto treadmills, felt the moist skin inside their wrists to measure their pulses, used cold, metal calipers to pinch and measure their body fat.

Jon wanted to wait for the pregnancy to happen naturally. Not me. Waiting seemed like a waste of time. I’d gone to several doctors and they all said it wouldn’t – no, simply couldn’t– happen naturally. Jon didn’t believe that medical intervention was necessary. He felt like fertility specialists pushed immediate action to make money, that the whole thing was more or less a scam.

One day, Jon admitted that he wasn’t ready for a child, let alone the stressful and expensive path we’d have to take in order to have one. That’s the thing about meeting your spouse when you’re so young. You don’t know what your future self will want, which sacrifices you will be able to make, which ones you won’t. My baby fever had come on so quickly, and I understood that it had taken Jon by surprise. I assumed that he’d come around, eventually, yet my patience was wearing thin.

I thought I could overpower his logic with my tsunamis of emotion, but he felt rushed – like we had time, like we didn’t need a baby any time soon. “What’s the rush?” he wanted to know. The rush, I told him, was that I had so much love to give a child that it physically hurt me not to be able to give it. The rush, I said, is that I need this – that I am nobody without this. The rush is that I need my family to grow, that I am not complete with just you to love, with a man who sees me fold into myself and cry on a daily basis because she feels incomplete and who still feels like it’s perfectly acceptable to ask me, with no conflict of conscience: “What’s the rush?”

One day, Jon told me he wanted to put a second story on the house. This would be expensive and time-consuming and inconvenient. How could he have wanted this, but not want a baby? We were not seeing eye to eye. Our priorities were different. We were not compatible.

One night, after we’d argued about the baby versus the house addition for the fiftieth time, we agreed that we’d had enough. We decided we’d give it a year. If after this year, I still wasn’t pregnant, and he still didn’t agree to fertility treatments, we’d split up. It was the closest thing to a compromise we could come up with and both felt that it was fair.

At this time, an endocrinologist put me on antidepressants to help me with mood swings which she attributed to a spastic thyroid. “This might also work for – other things,” she added. I took them for the “other things” — not even knowing exactly what these other things were but knowing that I needed something inside me to be fixed. They worked almost immediately. I felt calmer, less in limbo. Some people say that these drugs make you numb. I wasn’t. I was full of energy. I got a promotion at work. Unexpectedly, I started getting my period again. I was so content that I almost forgot about the ache in my heart.

Several months later, my period a week late, I stopped at Walgreens on the way home from teaching an early morning Spinning class and bought a pregnancy test. When I saw the faint appearance of the second red line, I didn’t even bother pulling my underwear back up. I ran into the bedroom where Jon was sleeping, pee trickling down my leg, to give him the news. He was so tired, but he seemed happy. No, he was happy. Becoming a parent had not been his desire – not yet – but he hadn’t wanted to break up and this meant that we wouldn’t need to. I called my parents in New York, followed by my sister in California where it was just 4:30 a.m. I knew that the customary thing to do was to wait three months before telling people but I couldn’t even wait three minutes.

I had stopped taking antidepressants the moment I found out I was pregnant. Although I hadn’t been on them long, I had trouble without them, especially after my initial excitement wore off and the pregnancy hormones began raging. Every time I allowed myself to get excited about motherhood, I would deflate, for one reason or another, a mild fog of pessimism finding its way into the empty spaces throughout my day. Maybe it was because I knew that Jon didn’t want to be a parent as badly as I did and that this was, essentially, my own journey, my own project. I had worked so hard at establishing a life away from my family, but maybe that had been a mistake. Maybe I couldn’t raise this baby without them, especially because my partner didn’t share in my excitement.

“I’m sorry,“ I whispered. “I will love you enough for the both of us.” .

The day I found out I was having a girl, the too-good-to-be-true feeling intensified. The baby of my dreams had always been a girl. I knew what it would feel like to hold her small body close to my beating heart, to press my cheek against hers, to lather up her tiny back in the bath, shoulder blades white with bubbles, glistening like angel’s wings. After the gender-determining ultrasound, I went to lunch at a Greek restaurant near my doctor’s office and sat outside at a table, dipping pita into hummus. I ordered a Greek salad and called Jon from my cell phone.

“I want to say I’m happy about this,” he said. “But, I really wanted a boy.” It hurt, but I was used to my bubbles bursting. I was heartbroken but, for the first time since I’d become pregnant, I did not feel alone.

“I’m sorry,“ I whispered. “I will love you enough for the both of us.”

My parents visited for Thanksgiving. They took me to register for what I would need for the baby – things to help her sit when she couldn’t yet sit, stand when she couldn’t yet stand, walk when she couldn’t yet walk. Using an electronic scanner, we went around, zapping the barcodes on the dozens and dozens of items that the store’s eager saleswoman convinced me were necessary.

I left the store light-headed and overwhelmed, imagining our house filled with plastic, multicolored devices of varying shapes and sizes, cluttering the space with their polka dots and animal noises and battery compartments and thick instruction booklets with warnings large and bold and in so many different languages.

I had already committed my first sin of motherhood: letting someone else tell me what would be best for my child.

Back at home I went online, logged into the account I’d created and showed Jon everything I had registered for. He asked: “Why can’t you just hold the baby? Why do you need all this stuff?” And even though his comment echoed my own feelings, it hurt that he had said “you” and not “we”.

I still felt anxious a lot of the time so I found a therapist whom I saw weekly. She asked me what I was worried about. I explained how I worried about going back to work once the baby was born but was just as worried about not going back to work. Mostly, I was worried that Jon would not take an active role in raising our child. I also worried that my worry was causing her harm inside the womb. The only thing I was not worried about was how much I would love her.

The therapist, Laura, was a pretty blond, a little older than I was. I knew that she was married and did not have kids and I wondered if she wanted any, although I did not ask.

When I used the bathroom during our sessions, I would stare at myself in the mirror in the fluorescent light and try to see myself the way Laura was seeing me. She had never known me as a person who wasn’t pregnant and I felt like I was misrepresenting myself. “This is not really who I am,” I told her one day. “I am used to wanting a pregnancy, not having it, and I don’t feel totally worthy of it.” I explained that I felt like a lottery winner who finally finds herself rich, not entirely comfortable with her good fortune.

At around my sixth month of pregnancy something started to change. I felt more hopeful. The baby books all talked about increased energy in the second trimester. Was that all it was? For me, energy and happiness have always been somewhat synonymous. In the morning, after my first few sips of coffee, right as the caffeine hits me, I am filled with hope and excitement. It doesn’t last long, but it is powerful enough to make me look forward to the day. So maybe that was all this was: hope fueled by a feeling of wakefulness?

Laura told me that I looked different. She reminded me that when I had first come in, I was hunched over and clutching a pillow. I seemed somehow taller now, she said, my chest open and my shoulders back – like the cues I would give my fitness clients when lifting weights. At work, I was used to being an observer of people’s bodies and it felt strange to be observed. But it also felt reassuring, knowing that someone else had noticed a change in me, that it wasn’t just in my head.

You were born on a Monday night at 9:40 pm. You were so white – almost gray– when I first caught a glimpse of you and I thought you were dead until you began to cry.

“Try feeding her,” the nurse suggested, and I put you on my breast.